Perhaps the greatest impact of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring was the negative publicity that it generated for the pesticide DDT, which at the time was used both in agriculture and for public health uses to fight malaria and other insect-borne diseases. This negative publicity actually led many nations to ban or stop using DDT even in limited applications where it was needed to control mosquitoes and save lives. As a result, every year millions of people around the world die from malaria—needlessly.

Perhaps the greatest impact of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring was the negative publicity that it generated for the pesticide DDT, which at the time was used both in agriculture and for public health uses to fight malaria and other insect-borne diseases. This negative publicity actually led many nations to ban or stop using DDT even in limited applications where it was needed to control mosquitoes and save lives. As a result, every year millions of people around the world die from malaria—needlessly.

Some might deny Carson’s role in this scenario by pointing out a couple comments she made early in the book suggesting some pesticide use might be necessary. She notes:

“All this is not to say that there is no insect problem and no need of control. I am saying, rather, that control must be geared to realities, not mythical situations, and that the methods employed must be such that they do not destroy us along with insects.”

Who could disagree with this statement? Unfortunately, the rest of Carson’s harsh rhetoric about DDT led the world in the complete opposite direction. Carson discussed DDT in her chapter on “Elixirs of Death,” in which she postulates that man-made chemicals affect processes of the human body in “sinister and often deadly ways.” Regarding DDT, she concluded that “the threat of chronic poisoning and degenerative changes of the liver and organs is very real.” In a chapter on cancer, she says that one expert “now gives DDT the definite rating of a chemical carcinogen.”

Ironically, while Carson called for policy based on reason over myths, she opened her book up with a “Fable for Tomorrow,” describing a town in which chemicals have destroyed wildlife and people die from chemical exposures. She admitted it doesn’t exist, but somehow we are supposed act on her myth because, “It might have easily have a thousand counterparts in America.”

But Rachel was wrong. Humans were exposed to massive amounts of DDT without showing ill effect. And unlike Carson’s fable, malaria is a harsh reality today, killing more than a million people a year and making 300 million seriously ill, mostly in the developing world. Follow the links on this page to learn more about the malaria crisis and how DDT could help remedy the problem.

What is Malaria?

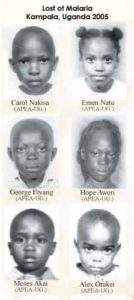

Malaria is often a fatal disease caused by a protozoan that is transmitted to humans via mosquito bites. According to the World Health Organization, malaria has killed more than a million people a year—mostly children—and makes millions seriously ill (although rates have declined significantly in recent years). Most malaria’s victims live in Africa, and most of them are children under the age of five. During the 1990s, in Africa, one in 20 children died from malaria, according to one estimate. The malaria death toll is equivalent to about 3,000 children dying from the disease a day—which amounts to one child dying every 30 seconds. “The malaria epidemic is like loading up seven Boeing 747 airliners each day, then deliberately crashing them into Mt. Kilimanjaro,” noted Dr. Wenceslaus Kilama, chairman, Malaria Foundation International.

Malaria greatly hinders development in places like Africa, exacerbating serious problems associated with poverty. In addition to placing demands on health care where such is even available, malaria makes it impossible for millions of people to perform vital functions in African economies. According to the Roll Back Malaria Campaign, malaria can account for as much as 40 percent of government public health budgets. Malaria programs cost African nations an estimated $12 billion a year and consume 25 percent of poor Africans’ family budgets. In some nations where malaria outbreaks are most severe, malaria accounts for up to half of hospital admissions and outpatient treatment.

The DDT Miracle

As far as we know, the type of malaria that infects humans does not infect wildlife, which means that the malaria parasite needs human hosts to survive. Accordingly, if human transmission could be prevented the malaria parasite would die off. This is unlike the West Nile virus which appeared in the United States in 1999. West Nile also infects birds and other species, and mosquitoes can then transmit the disease between humans and these species. Accordingly, West Nile can reside in wildlife for years without human transmission and then reappear among humans sporadically. Because humans serve as the malaria parasite’s host species through which they reproduce and spread, efforts to prevent human exposure not only benefit the individuals employing such tools, they help in the larger battle to eradicate malaria.

The pesticide DDT—which is short for Dichloro-Diphenyl-Trichloroethane—have proven to be a critically important tool in reducing malaria transmission, practically eradicating malaria in some areas of the world. Paul Herman Muller discovered DDT’s insecticidal properties in 1939, which earned him the 1948 Nobel Prize in Medicine because his discovery provided a highly effective and affordable way to manage major public health risks carried by mosquitoes, lice, and other vectors. DDT has saved millions of lives around the world. It helped cleanse Nazi war victims of disease-ridden lice, and it was embedded in the uniforms to protect allied troops from vermin and typhus.

DDT was used to largely eradicate malaria from the United States and other Western nations, and was used with some success in developing nations as well. In 1955, the World Health Organization launched a global campaign to use DDT along with anti-malaria drugs to fight malaria in developing nations. One report in the Bulletin of the World Health Organization notes: “As a result of the Campaign, malaria was eradicated by 1967 from all developed countries where the disease was endemic and large areas of tropical Asia and Latin America were freed from the risk of infection. The Malaria Eradication Campaign was only launched in three countries of tropical Africa since it was not considered feasible in the others.”

In 1970, the National Academy of Sciences reported: “To only a few chemicals does man owe as great a debt as to DDT. It has contributed to the great increase in agricultural productivity, while sparing countless humanity from a host of diseases, most notably, perhaps, scrub typhus and malaria. Indeed, it is estimated that, in little more than two decades, DDT has prevented 500 million deaths due to malaria that would otherwise have been inevitable. Abandonment of this pesticide should be undertaken only at such time an in such places that it is evident that the prospective gain to humanity exceeds the consequent losses. At this writing, all available substitutes for DDT are both more expensive per crop-year and decidedly more hazardous to those who manufacture and utilize them in crop treatment for other, more general purposes.”

In 1975, Barron’s magazine (November 10, 1975, p. 3) pointed out the great benefits that DDT brought to public health, including reducing India’s death rate from 750,000 to 1,500 a year, helping eradicate malaria in the United States (where it was endemic in 26 states) and Europe. In addition, DDT helped control typhus, yellow fever, and sleeping sickness—all deadly diseases transmitted by insects. “ Perhaps the most remarkable success story,” note Richard Tren and Roger Bate, is Sri Lanka, where within 10 years of DDT use, malaria cases dropped from about 3 million a year to 7,300 eventually reaching just 29 in 1964.

DDT is still effectively used by some nations for malaria control. For example, Ecuador, which has increased its use of DDT since 1993, has the largest reduction of malaria rates in the world. South Africa relied on DDT until 1996, but then suffered from serious malaria outbreaks after it discontinued use because of environmentalist pressure. Amir Attaran and Rajendra Maharaj report that after DDT was discontinued in one province, “malaria cases then promptly soared, from just 4,117 cases in 1995 to 27,238 cases in 1999 (or possibly 120,000 cases, judging from pharmacy records.) Other provinces experienced similar catastrophes.”

Green Crusade Against DDT

With her book Silent Spring, Rachel Carson was one of the first people to suggest that DDT was creating widespread problems in the environment. Although there may have been problems with the widespread use of DDT in the environment and some expression of concern was warranted, many of Carson’s claims were highly suspect and her extreme rhetoric led to an overreaction in the other direction—policies to curb DDT use even where it was most needed for public health purposes.

At the time, a reviewer of Silent Spring in Science magazine (September 28, 1962, p. 1043) praised Carson for raising concerns about potential dangers associated with pesticide misuse, but the author expressed serious dismay with Carson’s extreme approach. The reviewer noted: “Just as it is important for us to be reminded of the dangers inherent in the use of new pesticides, so must our people be made aware the tremendous values to human welfare conferred by the new pesticides. No attempt is made by the author to portray the many positive benefits that society derives from the use of pesticides. No estimates are made of the countless lives that have been saved because of the destruction of insect vectors of disease.”

Because of the anti-DDT and anti-chemical hysteria engendered by the ideas in Silent Spring, DDT was eventually removed from the market under the Nixon Administration. Yet DDT was banned despite findings of an EPA panel that it was not a public health threat. Barron’s magazine (November 10, 1975, p. 3) reported on the topic in 1975: “In banning DDT, for farm uses, then-EPA director Ruckelshaus over-ruled the federal hearings examiner Edmund Sweeney. After seven months of hearings, during which 125 witnesses were called and 9,000 pages of testimony were submitted, Sweeney declared that the evidence indicated that DDT wasn’t a cancer hazard. He added that on balance, its usage did not create an unreasonable risk with its benefits…‘In my opinion,’ he said, ‘the evidence in this proceeding supports the conclusion that there is a present need for the essential uses of DDT.’” Similarly, Barron’s reported, the year before the ban, the National Communicable Disease Center of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare noted: “The safety record of for the use of DDT…is nothing short of phenomenal.”

The continued flow of misinformation about the public health impacts of DDT advanced by environmental activists along with the U.S. ban prompted public officials in other nations to stop using it and to even ban it in some places. In good measure, because of reduced use of DDT, malaria rates skyrocketed by the 1990s after having reached historic lows in the 1960s while DDT was in use. Roger Bate and Richard Tren note, for example, in Sri Lanka, which stopped using DDT in 1964, cases rose from a low of 17 to about half a million by 1969. Donald R. Roberts, MD, of the U.S. Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences and his colleagues note: “Although many factors contribute to increasing malaria, the strongest correlation is with decreasing number of houses sprayed with DDT.” A study of malaria in Latin America demonstrates a causal link between DDT spraying and malaria rates.

This study also shows that when global efforts to control malaria began to reduce emphasis on vector control (i.e., DDT), the malaria problem grew. The authors reported that “countries that discontinued their house-spray programs reported large increases in malaria rates. Countries that reported low or reduced HSRs also reported increased malaria. Only Ecuador reported increased use of DDT and greatly reduced malaria rates.”

Despite the devastating toll associated with reduced use of DDT, many government agencies and environmental activists have been reluctant to change their views. Even where DDT is allowed, government aid agencies—including some at the U.S. Agency for International Development—have denied funding to nations if they chose to use DDT. In 1990s, the United Nations Environment Program began work on the Convention of Persistent Organic Pollutants (known as the POPs Convention), which set in place bans on 12 chemicals, including DDT. However, during negotiations on this treaty, public health officials finally spoke out on the DDT issue, urging the governments to at least allow limited DDT use for malaria control. To that end, they signed an open letter urging POPs Treaty negotiators to include a public health exemption to the DDT ban. As a result, the final treaty allows for a temporary, limited exemption for DDT use for malaria control. But even with its limited, temporary exemption, the treaty regulations governing use make access more expensive.

In 2006, the World Health Organization decided that DDT use should again become an important part of malaria control programs, noting in a press release: “WHO actively promoted indoor residual spraying for malaria control until the early 1980s when increased health and environmental concerns surrounding DDT caused the organization to stop promoting its use and to focus instead on other means of prevention. Extensive research and testing has since demonstrated that well-managed indoor residual spraying programmes using DDT pose no harm to wildlife or to humans.”

Unfortunately, while DDT use has increased in some areas, particularly South Africa, where it is having positive impacts, its use is still limited in part by negative public perceptions about DDT and its risks.

DDT for Malaria Control

DDT is among several tools used today to fight malaria in developing nations. Other tools include bednets, medical treatments, and other pesticides. However, DDT has proven to be most affordable and effective tool and for this reason should remain part of malaria control programs. In 1990, DDT was determined to cost two to 23 times less than other alternatives, and recent assessments find that it remains the most affordable insecticide (see: K. Walker, Cost Comparison of DDT and Alternative Insecticides for Malaria Control,” Medical and Veterinary Entomology 14, 2000: 345-354). Sadly, DDT prices have increased because of declining production, which is related to political campaigns to regulate and ban the substance.

As far as we know, the type of malaria that infects humans does not infect wildlife, which means the malaria parasite needs human hosts to survive. Accordingly, if human transmission could be prevented the malaria parasite would die off because of the lack of access to hosts. In most of developed world, public health officials eradicated malaria by preventing human exposure in large part through DDT programs. In addition, development also greatly reduced transmission of all types of mosquito-borne diseases because most people in developed countries now live in sealed homes—homes with screens and sealed windows that keep mosquitoes out. Air conditioning also plays a role because it enables people to keep windows closed.

In developing nations, controlling malaria is much more difficult because mosquitoes have greater access to the insides of homes. Mosquitoes enter homes—huts and other unsealed structures—freely and feed on people at night while they sleep. The use of insecticide-treated bednets can be helpful, but the benefits have been limited for a number of reasons: the nets are expensive, are often not used properly, can become damaged, and must be retreated or replaced relatively frequently. In addition, people often choose not to use them in hot climates because they reduce ventilation.

DDT is particularly helpful in these conditions, requiring limited applications where people live, rather than widespread application in the environment as was common in the 1950s and 1960s. Today, public health officials can spray DDT in and around huts and other residential structures to prevent human exposure in large part by repelling mosquitoes. In essence, DDT acts as a chemical “screen,” keeping mosquitoes away and killing the few that might enter homes. It also does not require that people do anything to make it work each night, and it’s relatively inexpensive. Because DDT is persistent (i.e., it does not break down quickly), it works a long time without the need of constant reapplication. Ironically, DDT is subject to regulations and bans around the world because of its persistence in the environment; yet this persistence is one of DDT’s key public health benefits.

Is DDT Safe?

Despite the fact that DDT was banned without public health justifications, many people still believe it is dangerous to public health. While Rachel Carson did not rule out some limited use of DDT, she greatly contributed to perceptions that it was dangerous, which advanced extreme approaches like government bans. In a chapter titled, “Elixirs of Death,” she claimed that while DDT might not be toxic in a powder form, it is “toxic” in other forms and when ingested. And she said because it is stored in tissue, its accumulation means that the threat to poison and produce degenerative diseases in organs is “very real.” In the chapter titled “One in Every Four,” she claimed that cancer rates were climbing and would continue to climb because of the use of chemicals, including DDT.

While Carson could offer no definitive science on the issue, she offers anecdotes that imply problems caused by DDT. For example, she describes a man who after spraying for cockroaches using a product containing DDT suffered from hemorrhaging. The man was eventually diagnosed with leukemia, which eventually led to his death. There is no evidence that his illness had anything to do DDT use, but Carson attempts to link the two. She also notes that one researcher gave DDT a “definite rating” as a “chemical carcinogen” based on lab tests that produced tumors in rodents. However, none of Carson’s findings in these chapters amounted to anything more than speculations that offer nothing in terms of scientific value.

Since the findings of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) committee in the 1970s that reported no public health problems arising from DDT, there remains no compelling evidence that DDT has produced any ill public health effects. In 1990, an article in the medical journal The Lancet reported: “The early toxicological information on DDT was reassuring; it seemed that acute risks to health were small. If the huge amounts of DDT used are taken into account, the safety record for human beings is extremely good. In the 1940s many people were deliberately exposed to high concentrations of DDT thorough dusting programmes or impregnation of clothes, without any apparent ill effect…In summary, DDT can cause toxicological effects but the effects on human beings at likely exposure are very slight.” In any case, the risks of using DDT should be weighed against the very real life-and-death risks of malaria.

Several studies have attempted to link DDT with some cancers and other problems, but have failed to show a conclusive link. In particular, a number of studies have sought to establish a link between DDT and related pesticides and breast cancer, claiming that these produces disrupt endocrine systems and produce breast cancer. One study claimed to find a link in 1993, but it was deemed not definitive in part because of its relatively small sample size. Subsequent studies of greater scope could not find a link. The National Research Council concluded in 1999, in a report reviewing the “endocrine disruptor” issue, that the original breast cancer study and all the ones published before 1995 “do not support an association between DDT metabolites or PCBs and the risk of breast cancer.” More recently, U.S. researchers produced one of the largest and most comprehensive studies ever on the topic, assessing the impact of pesticides on breast cancers among women in Long Island, New York. This research could not find a link between the breast cancers and the chemicals most often cited as the problem (DDT and other pesticides as well as PCBs).

There has been similar focus on the potential for DDT to impact children through their mother’s breast milk. However, again, there is little evidence of such problems actually existing. Malaria experts Amir Attaran and Rajendra Maharai point out that researchers have not found any detectable health effect on babies from traces of DDT found in breast milk. Moreover, the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Expert Committee on Malaria noted in 1995 that such concerns are not relevant to DDT use for malaria control because they did not find evidence that the use of DDT to control malaria would have any such adverse public health effects. Accordingly, the WHO noted that DDT should remain a tool for controlling malaria despite concerns about its appearance in breast milk.

While the risks of DDT to newborn babies through breast milk exposure are insignificant, malaria presents far greater risks to newborns. The Roll Back Malaria campaign notes for example: “In Malawi, where malaria is the leading case of illness and death, up to 40 percent of women pregnant for the first and second time have placental malaria at the time of delivery, resulting in increased incidence of low birth weight and higher mortality for newborns and infants.”

DDT and Wildlife

The debate about whether DDT had a serious impact on wildlife is less clear. There is some evidence that widespread DDT use in the environment appears to have affected the ability of some birds of prey to reproduce, according to some sources. However, others claim that such problems were either overblown or that they are unfounded. In either case, the concern about DDT’s impacts on wildlife not related to public health uses of DDT that involve limited application to homes rather than environmental applications. As noted, residential uses of DDT can greatly help break the malaria transmission cycle without application in the environment and without adverse impacts on wildlife.